Om trapetssegling

– en artikel i GKSS

medlemstidning Seglarbladet, Nr.6 1963

Snabbt framrusande båtar som seglas

med gasten hängande utanför båten i en vajer från masten har numera

blivit en vanlig syn utanför Långedrag. Många äldre seglare, fiskare för

att icke tala om landkrabbor skakar på huvudet, men andra tycker det ser

trevligt och sportigt ut och skulle gärna pröva om tillfälle gavs.

Första steget mot detta sorts segling togs för inte så många år sedan

vid tävlingar mellan kanadensare och britter i 14 fots jollar, då endast

en lina med en stor knut på användes. Nu är båtarna utrustade med en

vajer på varje sida om masten. En resårlina håller vajern – trapets

kallad – på plats då den icke användes. Vanligen finns en stor ögla i

ändan på vajern så att den kan krokas fast i ett bälte som ofta är

utformat som en slags byxa med en kraftig krok i ett platt beslag

framtill.

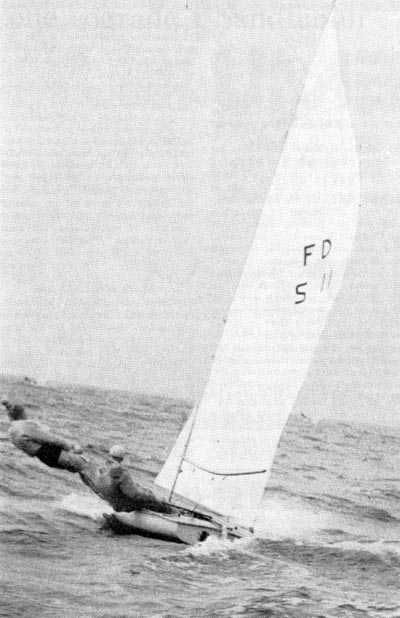

I sommar kommer kappseglingspubliken vid tribunen att bli välbekant med denna sorts segling, då viga gastar kommer att vara i aktion på åtminstone 7 Flying Dutchman och ett femtontal 5-0-5.

Konstruktören av 5-0-5, John Westell, har skrivit en belysande artikel i ämnet och Seglarbladet är här i tillfälle att återge den i översättning.

Innan jag hade någon vidare erfarenhet av trapets, tillbringade jag tusentals timmar hängande ut i racerjollar på det vanliga sättet med fötterna under krängstropparna, relingen skärande in i låren och magmusklerna klagande att de var trötta redan före starten. Sedan jag provat med vilken lätthet och bekvämlighet man svänger i en trapets har jag inte längre den ringaste önskan att återvända till mina tidigare uthållighetsprov. Folk som aldrig använt trapets uttalar ofta farhågor att båten skall kränga över mot lovart och trycka ner dem under seglen, men enligt min erfarenhet händer detta ytterst sällan.

En gång när vi kom med hårdskotade

segel uppför

the Crouch för sydvästlig vind med Clarence Farrer i trapetsen, fick

vi plötsligt back i focken och storseglet slog stopp. Vi blev

fullständigt överrumplade, båten rullade över mot lovart, så att

Clarence svängde ut 10 fot utanför relingen i ändan på vajern, men när

vi hade rullat över så långt att han var nere till halsen togs hans

tyngd upp av vattnet och vi rullade icke mer. Jag krängde mig fast på

läsidan och när vinden släppte rullade vi tillbaka igen. Clarence

dunkade hårt mot relingen men var genast oförskräckt ute igen i hela sin

längd i trapetsen. Samtidigt hade jag samlat ihop skoten och fått gång

på båten.

Tekniken att använda en trapets är mycket enkel att lära sig, i själva

verket så enkel att jag tagit med mig en ung flicka ut som icke hade

någon tidigare erfarenhet av att segla småbåtar och hon fann nöje i

livet i trapets inom 20 minuter efter det vi lämnat land. Ej heller

behöver en trapetsgast vara speciellt vig. Bland de skickliga

besättningarna finns det åtskilliga män som passerat de 50.

Trapetsvajerns längd bör avpassas så att vajern lätt övertar tyngden på

kroppen när gasten lutar sig helt ut med fötterna under krängstropparna.

Den får inte vara så kort att kroppen helt lyfts upp över reling eller

däck. En för kort vajer gör att gasten får ett allt för upprätt läge

vilket ger onödigt vindmotstånd och lämnar mindre krängande kraft. Det

är också riskabelt eftersom en oförsiktig gast kan missa lovartsidan och

hamna i lä. När vajern och bälte passats till bör den blivande

trapetsartisten göra sina första försök en dag när det blåser en frisk

stadig bris. Det är enkelt nog att använda trapetsen i mycket byig vind,

men första gången blir det hela lättare i jämn vind. Lämnade utan

instruktion startar nästan alla med fullständigt fel teknik: de försöker

ställa sig upp på lovartsidan innan de lutar sig ut, vilket är

förkastligt.

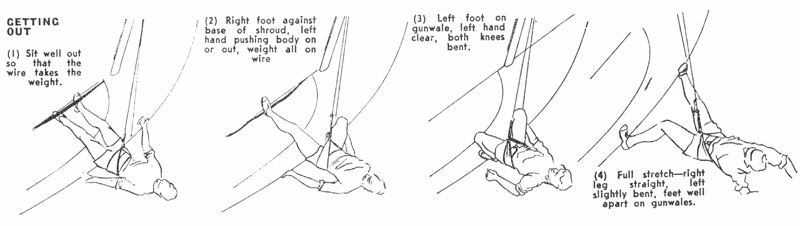

Den korrekta metoden är att haka fast vajern och luta sig tillbaka i

normalt sittande ställning. När man känner sig tillrätta så, med det

mesta av kroppsvikten i vajern och benen fortfarande inombords kan man

försöka nästa stadium. Man drar upp främre benet och med en lätt

vridning av kroppen framåt, sätter man foten på relingen intill staget.

Skjut med bakre handen mot relingen ut kroppen så långt att endast ena

benet är kvar inombords. Främre benet är fortfarande böjt. Detta är en

mycket fördelaktig position eftersom man kan svänga in och ut mycket

snabbt. Sista momentet är att sätta aktre benet på relingen och sträcka

benen så man ligger rätt ut.

Om båten stampar är det risk att man bringas ur balans så att man

svänger in över fördäck. En del motverkar detta genom att sätta främre

foten litet för om staget, men man riskerar då att skada benet, om man

måste svänga in plötsligt. De flesta kommer ifrån svårigheten genom att

luta sig en aning akterut med främre benet sträckt och lätt böjt bakre

ben, på samma gång som de håller sig i fockskotet. Mindre växlingar i

vindstyrkan tas upp genom böjningar och sträckningar på bakre benet

medan kroppen väges mot främre benet som hålles rakt.

För att komma in igen på riktigt sätt låter man aktre benet glida över

däcket och aktre handen tar emot på relingen så att man dämpar stöten.

Det är ingen konst att komma fint och snabbt under full kontroll ens

från helt utsträckt läge.

Foten måste få bästa möjliga fäste på den våta relingen så man inte

slinter när båten gungar och kränger. Dunlopskor anses vanligen vara

bättre än nakna fötter och relingen bör vara halkskyddande. Ett gott

samarbete mellan gast och rorsman är viktigt för ett viktigt

trapetsarbete och de måste vara överens om vilken lätt krängning båten

skall ha. En lätt krängning på FD är ofta det bästa (medan 5-0-5 alltid

skall seglas så plan möjligt). Om rorsman vill ha litet krängning och

gasten kämpar för att räta upp båten så kommer ingen av dem att känna

sig belåten.

Det är bäst för rorsman att hänga ut bekvämt och stanna så och helt

överlämna åt gasten att trimma båten så långt det är möjligt för honom

att röra sig in och ut. Skepparen bör göra det till regel att upprepade

gånger säga till innan han slår, så att trapetsgasten kan komma in och

haka loss innan slaget börjar. I nödfall får han lägga rorkulten i lä

och hoppas på det bästa. Det bör fortfarande vara möjligt att hålla

båten mot vinden så länge, att gasten, som dykt inombords i panik,

hinner koppla loss vajern och klara focken.

Det är hela hemligheten med "trapetsning". Passa till grejorna på rätt

sätt och skaffa det rätta förtroendet för vajern i lugn och ro. När ni

finner att ni ej längre frenetiskt griper i den utan kan använda

händerna bättre kommer ni att uppskatta nöjet att hänga ut väl över

planingsvågen och se hur skummet yr över skepparen som förut tog skydd

bakom er. Man kan inte få ett bättre ställe att uppskatta en femton

knops planing än sex fot utanför relingen. Man kan se hela skrovet plöja

och rusa genom vattnet och när båten för ett ögonblick löper fri ifrån

vattnet kan man se dagsljuset under och hur bladen på centerbord och

roder skär vattenytan som fenorna på en haj.

JOHN WESTELL

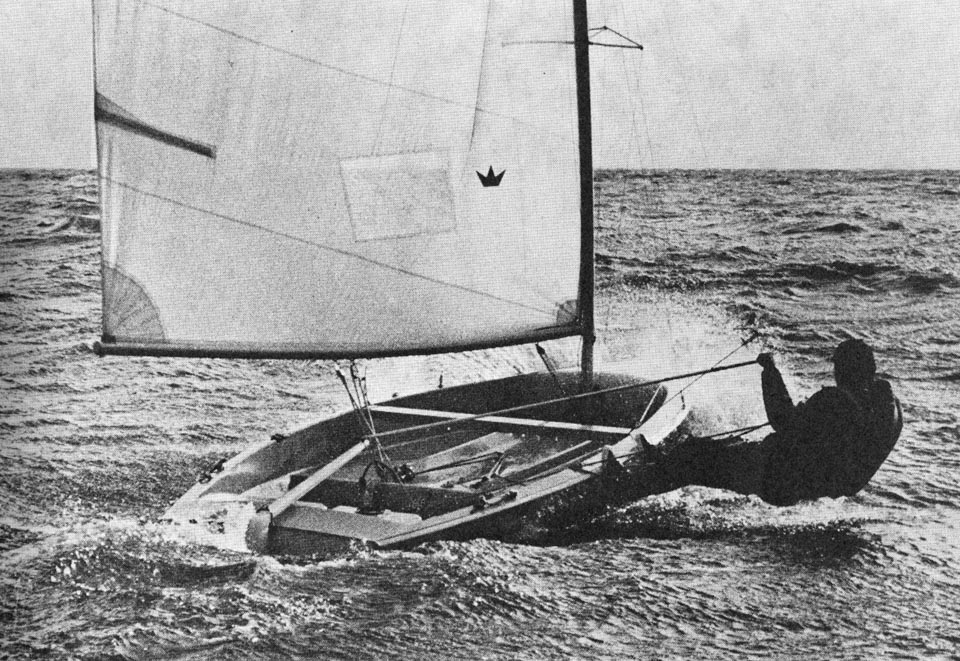

John Westell crewing in the trapeze with possibly Bruce Banks at the helm sailing back into the mouth of Hamble. Corona was a famous early 505 and raced at Ouisterham in Northern France, having made the trip cross channel in the back of a powerboat. Photo taken by Eileen Ramsay.

After half a dozen years of abstinence and mounting desire, in 1966 Elvstrom returned to international competition in an explosion of success. He was first lured back by one of his good crewmen, Pierre Poullain of France, who suggested casually one day that they should give the forthcoming world championship in the 5-0-5 class a fling, seeing that it was being held just around the corner in Adelaide, Australia. Alors, why not? Without really caring, Elvstrom agreed, largely because he wanted to try out a fancy idea that had come to him while reading the fine print of the rules for that class.

In their previous outings together Elvstrom had needled Poullain for being a mere 150-pound mosquito who really did not have enough weight to throw around when hanging on a trapeze – that precarious rig that allows a heavy racing crewman to hang from the masthead well outside of his boat and thus keep it upright. Elvstrom noted that the rules for the 5-0-5 class forbade the use of more than one trapeze, but it did not specify who aboard the craft should use the trapeze.

When Elvstrom and Poullain gathered with a number of European rivals to take a London flight out to Australia, the others saw Elvstrom carrying a tiller extension to which was connected something that looked like another tiller extension. "What is it?" they asked.

"It is a tiller extension to the tiller extension," Elvstrom said, and everyone laughed. Ha-ha – Elvstrom the Invincible returns to the wars as a jokester.

But, lo and behold, in practice before the races started, there was Elvstrom throwing his 185 pounds of weight around as crewman in the trapeze, and at the same time, by means of a double-length, double-jointed extension to the tiller, serving also as helmsman. "When we race," Elvstrom instructed his crewman Poullain, "your most important concern will be not to fall out of the boat."

Because his father died, the Frenchman had to return home before the championship began and Elvstrom picked an able-bodied Australian seaman, Pip Pearson, off the beach to take his place. Although they capsized once and floundered around in 12th place in another race, they took second. (By beating Elvstrom in that championship, Wine Salesman Jim Hardy of South Australia joined Andre Nelis of Belgium, Mario Capio of Italy and Jacques Lebrun of France in yachting's most exclusive club. At that time they were the only four helmsmen who have ever won a world competition in which Elvstrom of Denmark also took part.)

That same year, his first time at the helm in international competition in the 5.5-meter class, Elvstrom won the world title. One month later he won the Star title, defeating Lowell North of San Diego, one of the few three-time winners in the long history of that class. North remembers: "Although Elvstrom was leading in points, the night before the fourth race he spent hours working on his boat. He moved the mast around and changed the rigging. I would never rerig a boat that was going well in the middle of a series like that. Three times out of four it will slow down the boat." continue reading...

Paul Elvström: "Five-O-Five är min favoritklass därför att båten är så livlig och mottaglig för påverkan i all slags vind och i all sorts sjö."

When West Country dinghy sailor John Westell had been thinking about designing a boat for the Trials, through his friends Bruce Banks and Charles Currey, he found his way to none other than Austin Farrar. Farrar had designed an International 14 with widely flared topsides that had, like the trapeze, been promptly banned by the class. Read more...

Although most of the credit for the trapeze goes to Peter Scott and John Winter, Austin Farrar conducted much of the practical development to make this into a usable technique - photo © Farrar / Chivers Collection

läs och se mer:

»

Fler

tillbakablickar