It is a workable proposition that the front ends of national

and international dinghy fleets (and for good measure some keelboat fleets) are stocked

not with complete madmen but with some men who are so dedicated to sailing that their

sense of proportion has gone askew. 'The boat takes all' is no doubt a winning philosophy

but it is not a comfortable one.

It is a workable proposition that the front ends of national

and international dinghy fleets (and for good measure some keelboat fleets) are stocked

not with complete madmen but with some men who are so dedicated to sailing that their

sense of proportion has gone askew. 'The boat takes all' is no doubt a winning philosophy

but it is not a comfortable one.

If you are overawed or indeed jaded by such people, you should meet Phil Milanes. He is a doughty and competitive dinghy sailor whose often misprinted name keeps re-appearing at or near the front of the fleet: he has, for instance, won the Endeavour Trophy, and typically he popped up early this year to finish second in the Burnham Icicle.

Nevertheless it is reasonable to describe his attitude as healthy rather than ultra-competitive: he is a serious, but not an over-serious sailor, who continues to get much enjoyment and excellent results not by the calculated use of hard graft but by the happy use of his considerable experience and by the exercise of his natural sailing talent. It would be cheerful to think that there were many more sailors as successful as he who sail for fun and with such panache.

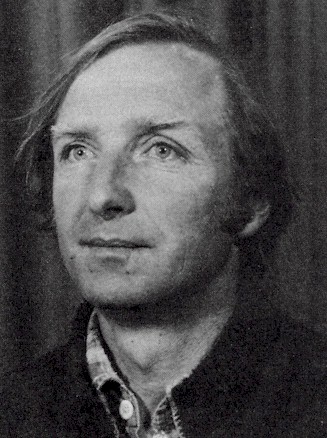

Phil has just turned 39; he stands 5ft 7in and his weight wavers around the 11 stone mark; he has soft blue eyes and a mop of markedly untidy blond hair. To be interviewed he wore the type of jersey that a wife will thankfully spirit away to the Oxfam shop while her husband is safely out of the house.

The first adjective to describe him is happy-go-lucky; but this is not fair, because he is a great deal more organised that he seems. He had, for instance, written out for the interview some of the salient points of his career with dates, a process as unusual as it is helpful; and, spurning big business, he has set up and now most successfully operates a nautical cottage industry which makes centreboards and rudders. Words tumble helter skelter out of Phil, many of which are amusing; without prompting he described himself as, a romantic, which can thus be taken as a true assessment, or at least as a reflection of how he sees himself.

Phil's family is of Spanish descent; his surname is pronounced as if it were spelt Milanaise (like Spaghetti Bolognese' said Phil helpfully). Phils father was in the Army, which accounts for Phil having been born in Peshawar in what was then India but is now Pakistan. The family stayed there till the partition of India, when Phil was six. It was from his extreme youth that his other great love, which is of mountains and of climbing came to be born.

He explained: 'I was told by my parents � my mother was a very good climber � that I used to wander up the mountains and hillsides from a very early age; and I was very, very impressed by the mountain scenery because, you see, we lived in Gilgit which was up in Kashmir.'

On coming back to England they lived in Keyhaven, 'we had a superb view straight over to the Needles' Phil recalls. He went to Sevenoaks School, where he was a reasonable rugby football and cricket player; he enjoys both games and has continued playing club rugby till recently. He left school at 17; he hoped that his geography A-level would allow him to become a geologist, but decided to settle for the timber trade as this would give him chances of travel. His family had by that time moved to Bosham and he joined the Chichester firm of David Cover and Son where he served a five-year apprenticeship, which included managing an outside yard and going to Sweden. He than decided to have a break and travelled overland to Pakistan, mainly by the use of local buses.

'I wanted to get back to the mountains' he explained with fervour. 'I wanted to go and possibly live in the mountains for a year or two; basically my first love, extraordinary though it may seem, is mountains. I yearn for them all the time: I love to climb them, be among them, and I love the atmosphere � the quietness, the sound of the pines � mountains really do get me.' He stayed in Pakistan for nine months and when not communing with the mountains worked in a marble and a rubber factory.

He returned to David Cover in Chichester but after 18 months joined the London timber firm of W.C.Ware, working first in London and then in Guildford. He worked there for some seven years, mainly on the sales side. He worked for two more firms in the timber trade, travelled all over Europe and made three visits to Africa before he began to think of starting his own business. 'I was disenchanted with the power politics of big business' he said 'I really wanted to get away from people in the power game and be my own boss.' Making centreplates and rudders had been a hobby: it grew imperceptibly so that he saw that it could become a business. He decided to make a physical break with London and chose the Wiltshire village of Urchfont, where he had a friend living, and for the excellent reason that he enjoyed the local Wadworth's beer.

He has not regretted the choice. Urchfont is calm and beautiful and looks like a Hollywood film set of an English village. Phil said that he thought he must be 'one of the original all-time bachelors'; but nevertheless he capitulated five years ago to his wife Clare, who was a Wayfarer sailor, and is now a happily married man who much enjoys his domesticity. They have two daughters; Katie, who is three, and Sophie, who is a mere year. The family now lives in a modern bungalow, hut they are in the process of negotiating for a seventeenth century cottage elsewhere in the village which they find to be an exciting prospect.

Phil started sailing with his family (he has two younger brothers) in what he called 'an old banger of a boat' at Keyhaven. He progressed to his own Cadet at about the age of nine. 'There were three or four others in Cadets', he recalled 'and in those days we were very evil. We used to terrorise the other local shipping, drive them up banks, it was horrific. We used to go in for capsizing competitions � you know, how many deliberate capsizes you could do in a summer. I think I got up to about one hundred. Stupid game.'

The change came when the family moved to Bosham and Phil, then about 18, acquired an elderly Firefly with aluminium decks ('would you believe it' he asked) and started racing in earnest. He then had a new Firefly, called 'Bop' after his love of modern jazz, and finished a very respectable fourth in his first national championship ('a lot of fourths I've had, it runs all through'). In his second Firefly, 'Spaghetti' sail number 3146, which he also built, he narrowly missed the championship, finishing a very close second at Llandudno.

After his Fireflies Phil moved straight into a Flying Dutchman and admitted: I was terribly lost in the first year'. He had four Dutchmans altogether, sailing a four-year stint up to the Olympic trials in 1972, in which he finished fifth. He says that what success he had he owed to his very aggressive crew, Peter Morton.

'If only we had campaigned and prepared ourselves a damned sight more effectively' he said 'we would have got further. The story of my sailing life is, I think, bad preparation; if anything ever comes out of this interview like "How not to win a championship" or "How not to prepare", it's follow me! I enjoy life too much, that's the problem. I like the other side too much, like drinking and socialising, and I sometimes can't stand the more serious side of my sporting activities.' He said that part of the difficulty has been the exceptional quality of the opposition: Mike Arnold in the Fireflies, Peter Colclough and John Loveday in the 505s and Rodney Pattisson in the Dutchman.

After his Olympic Flying Dutchman campaign he took a year off ('the tuning-up in small fleets nearly destroyed my faith in sailing'). 'It was probably the best year in my life when I packed up sailing', said Phil, 'I went off climbing every weekend and went to the Dolomites, the Alps. We were following some of the classic routes, and we got up to Extreme standard in climbing parlance. This is quite significant, though it isn't to someone who does not know what is involved.'

In 1974 he was propelled back by Willie Hartje into sailing a 505 although, as he explained, 'I was very reluctant to be dragged back into sailing � it took a lot of persuasion by him and other people'. The surprising and perhaps typical result was that he won his first open meeting and finished fourth in the national championship that year. He has sailed 505s ever since, enthusiastically buying a new boat every year or more frequently; he has not fallen below fifth in the national championship for the last five years, and last year he was seventh in the world championship and first British boat.

'For me anyway,' he said, 'the Five-O is the top boat: I prefer it to the Flying Dutchman and any other dinghy I've ever sailed in; it's totally fulfilling for me.' Now a Bosham friend, Johnny Falkner, has provided a Soling for the Olympic trials, for which Phil is the helmsman.

'Basically I have no wish to sail big boats' he explained 'but in the end Johnny persuaded me that it might be a good idea. I didn't want to campaign an Olympic boat too long, having known the miseries of a four-year campaign before; but this was only a short one. I just can't devote one hundred percent of my time to boats: I'm not made that way, it doesn't interest me enough. I love sailing basically, and I forget about all the bits and pieces on the side. This is why I come second; but one of these days I shall have a championship.' They now have a new Soling, which it is to be hoped his crew will tune up, and Phil is looking forward very much to sailing against the top men in the Soling fleet. He is not at all scared at the prospect of the Soling experts, and says that although he does not like the sensation of sailing the boat he enjoys the challenge.

His centreboard and rudder business started because Phil was always good with his hands ('I was born with artisan's hands') and he jumped at the idea of his own business to rescue him from the higher echelons of the timber trade. He had gone as far as he could without reaching the higher managerial or directoral level ('it didn't really interest me � I saw what it did to some directors and I knew that I would have to come up against people who were only interested in reaching the top because they loved power.')

He says that he enjoys producing beautiful articles shaped with precision and he added: 'I have a pride in something made with craftmanship.' He is now on his third workshop in the Urchfont district and has been joined as a partner by Peter White, who is an even better 505 sailor than he is, having been world champion once and runner up in the British championships three times.

About 70 percent of their output goes for export, and they produce 30 to 40 foils (centreboards or rudder blades) a month. They make for some 20 classes including Flying Dutchman, 505 and 470. He says that the principle of the rudders is simple in that they must be light and strong; about the centreboards he was secretive, saying guardedly that there were certain properties that a board should have, of which many people were not aware, including a certain amount of twist which must recover quickly.

'How you construct it and the shape that you make it is terribly important' he said 'and you must look for total perfection in the shape.' He says that all his experience of wood has been most useful and explained, 'I know a lot about the bending characteristics and stiffness characteristics of timber and I use them to what I hope is the best effect.' He is now also using carbon fibre and says 'if you use it in the right combination with other base materials it can offer tremendous potential.'

His firm is now working flat out, selling mainly to France, Germany and Belgium, and to several well known sailors in this country: he is, for instance, now making some foils for Rodney Pattisson. He says that he has had his problems and hardships but is untroubled by them. 'It's still a better form of life when you can plan your own scene and live where you want. I could never go back. Once you've tasted freedom there's no chance of going back: it's like a nightmare even thinking of it. Even if we should hit a really bad patch I would go and work on a farm just to get us over the lean period: anything rather than go back to big business.'

As a sailor Phil says that he is an instinctive one ('not as much brain power as some other people') and what he really enjoys is fast sailing. 'Aggression' he said surprisingly, 'is what gets me where I want to be: it comes out in my sailing, my rugger, my climbing.' He said that in building up his own business he does not sail as much as he wants to ('for the last two years sailing even at weekends has been a luxury for me').

He likes the big competitions and is now good enough simply to appear and do well without practice. He explained 'I rise to the competition: the more I'm frightened the better I do. If the top boys are around I tremble but I know I'm going to perform. It's the adrenalin, isn't it?'

It may well be that this splendidly cavalier approach will become known as 'doing a Milanes'; it has a certain very likeable magnificence, but regrettably can only be used by unselfconscious experts. Of his sporting activities Phil says that the parts that he has enjoyed most are climbing and sailing the 505; he says, with more honesty than tact, that if he had to choose between the two sports he would be forced to take up climbing; but socially, and because it is his business, he must stay with sailing, climbing being an even more anti-social and individualistic pastime.

His future sailing plans are simple. 'It's the 505s or nothing' he says firmly 'nothing else interests me: if it wasn't 505s I would revert to climbing'.

Is your rudder cracked, waterlogged or just plain rough? "Milanes Foils are suppliers of laminated or glass sheathed Sonata Blades, finely profiled and perfectly finished." (quote supplied by Phil Milanes).

Milanes Foils

www.milanesfoils.co.uk

Production: Unit 4, Station Yard,

Edington, Westbury, Wiltshire,

BA13 4NT

Mobile : +44 (0) 7814 115 975

Email:

[email protected];

[email protected]

— Sv.505 F�rbundet —

Uppdaterad 2020-02-22