|

The

post-Worlds party is always rowdy. On the Hyannis (Massachusetts) Yacht Club patio,

following seven days of world-class high-performance dinghy racing on Nantucket Sound, the

505 fraternity 200 plus sailors (almost all male), each with an implicit vow to reach

his way through life celebrates the class's forty-third world championship in typical

form: fast and fun. The party din smothers the sound of the band; a sailor streaks naked

waving an American flag; and a mischievous group prepares to toss the winners in the

water.

As the first American 505 world champions in 16 years, the

winners, Nick Trotman (Manchester, Massachusetts) and Mike Mills (Newport, Rhode Island),

are busy. Off in a corner, Trotman talks into a Cape Cod reporter's tape recorder. The

reporter asks the question the duo has been working to solve for six years: "How do

you win a world championship?" With a knowing grin, the 27-year-old Trotman responds,

"Speed kills."

Besides speed, 505ers seek fun and serious competition. There's a

lighter-side joke about 505 sailing: "We were having so much fun reaching, when we

got to the mark we just kept on going." There's a competitive side, too.

"Overbearing in victory, surely in defeat," an old regatta T-shirt reads. The

legends Paul Elvstrom's conquests in the 1950s, Swede Krister Bergstrom's four-year run

(1987-89 and 1991) at the Worlds, and, more recently, British dominance, including four of

the last five world champions inspire the top teams to find that extra gear of speed.

Most will agree that jumps in speed can't be found alone.

"You're only as good as your group," says Florida sailmaker Ethan Bixby. For

years the top Brits have capitalized on 60-boat regattas, group tuning, and short travel

for racing. Although the craze for newer high-performance dinghies in England has reduced

the size of their fleet, the core group, including world champions Ian Barker (1993) and

Mark Upton-Brown (1997) and 23 other teams that sailed in Hyannis, is still very active.

Motivated by a home venue and a rising group of college-trained sailors Trotman, Mills,

local Tyler Moore, Bristol Rhode Island's Mike Zani and his three-time North American

champion crew, Peter Alarie American 505 sailors teamed up to (heaven forfend they call

it training) "blast around." The American effort, on the weekends and at

regattas, was raised a notch on both coasts.

|

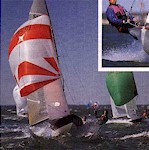

Race 4 is telling.

Trotman and Upton-Brown, tied in the series, round the first mark twelfth and fourteenth,

respectively. Both setting up high on the reach centerboard height adjusted critically,

mainsail flat and twisted, trapeze crew surfing the rail and working the spinnaker

they

start marching by one boat at a time. At the gybe mark, Trotman is eighth, the Brits

tenth. By the leeward mark, another clump of boats gone, they've both picked up two more

spots, looking to strike the top three. On the third (of four) beat, Trotman in fourth

sails left of the pack, while Upton-Brown heads far right. ("You've got to know how

to work the corners," Hamlin says.) The Yanks lead out of the left corner in a

favorable shift; they'll win the race. The Brits fade on the back side of the shift, and,

with three races to go, only Barker can stop the Americans winning the series.

After the race Mills explains the need for speed on a Worlds

course (14 miles, 9 legs). "It's a very long race, but the clock is ticking. You've

got to pass boats early and often."

|

The

POWERED-UP AND ENDLESSLY tweakable 505 was ahead of its time when it was designed by John

Westell in 1954. It is narrow on the waterline, but its flaring sides give it stability.

The mast/sail combination is powerful, and teams typically have a 200-pound crew on the

wire. (Bill Masterman, a 6 foot, 8 1/2-inch Brit, is the ideal for which every

skipper searches.) However, adjustable rig controls, mast rake, shroud tension, a

deck-mounted mast ram, and movable jib leads allow smaller crews and skipper to depower

and compete against the bigger teams.

And 505 sailors like to tweak. Skippers often take a

little-of-this, little-of-that approach to tuning. With experience, shifting gears is

automatic, but class newcomers are uncertain about tuning the 505. "At times we're

well-tuned, competing in the top ten," says 1996 college sailor of the year Tim

Wadlow. "Suddenly we're off a little and back in the sixties. And once you're

mid-fleet, you have to fight to stay there." In the parking lot, the sailors exchange

their settings of ram, rake and vang, noting, under the class's no-secrets policy, what

worked and didn't.

|

Barker, a full-time

sailor in England, discovered a racing element he didn't expect to find at the Worlds.

"Americans tune their boats for height. Europeans don't; we foot and sail fast. So in

a fleet that is one-third American, we found we had to change the way we sail upwind just

to keep lanes." By using gate starts, in which each boat starts on starboard tack

ducking the port-tack "pathfinder" boat, the 104-boat fleet starts evenly. So

being able to "hang in the initial drag race," Trotman explains, is critical for

a good finish.

The tweaking doesn't stop off the water. Although the 505 is

strictly one-design, there is room for development in sails, hulls, and foils. Many

players, for example, arrived in Hyannis with lightweight Kevlar mainsails. Ullman

sailmaker Jay Glaser, who has been designing 505 sails for 24 years, worked with Hamlin on

his latest Kevlar sails. Foils are even more open for development; the centerboard rule

specifies only that it must fit in the trunk. Baltimore lawyer and 505 lifer Macy Nelson

worked with Waterat's Larry Tuttle on a radical set of foils. His centerboard and rudder

are both high-aspect shapes, as much as 5 inches deeper than the average blades, designed

to generate more lift. The gains from such experiments are not easy to quantify, but half

the fun is trying.

|

|

Since the

popular hulls Rondar, Waterat, Kyrwood, Lindsay, Parker have similar shapes, 505ers

usually select boats based on material and cost. Most boats are foam-cored with Kevlar,

carbonfiber, or S-glass in the outer and inner skins. Speed differences in the

hulls?" At the end of the day the good guys win with any boat," says Ali Meller,

a computer analyst and class fireplug from Gaithersburg, Maryland. Trotman, sailing a

two-year old Rondar, practiced mainly with Newporter Tim Collins, who won race 2 in a

Kyrwood, and Zani, who sails a 1981 Lindsay, known as the "Dump Truck."

Around the dinghy park, Mark Lindsay-made 505s stand out from the

rest. His Kevlar-skinned performer redefined 505 construction in the late 1970s and

instantly rendered the time's polyester-resin boats obsolete. Lindsay wooden decks are

high maintenance compared to today's glass. And the popular launcher tube has replaced the

spinnaker-bag system. But the bulletproof hulls, which the Brits joke should be on display

in the Greenwich Museum, are still up to speed. "That's why we stopped building

them," says Mark Lindsay. "They don't go away."

As a

class, the 505 has the key elements of a lasting one-design a good used-boat market,

strong leadership, and a cliquish group of sailors. A lot of factors the Internet

(www.sailing.org/int505), Meller's persistent recruiting and marketing, non-Olympic class

status account for the class's strengths and recent growth. But success comes largely

from being a boat that is fun to sail and ever-fascinating for a lot of people. Ask any

505 sailors a 45-year old land broker, an ex-Olympian, a former Whitbread sailor,

76-year old Marcel Buffet, a past collegiate all-American and they'll all agree:

"The boat just feels right."

The 40-something lifers, most with 20 years of 505 tales and high

speed yawps, may not be as fit (or have as much time to train) as the younger guys, but

they're satisfied with a boat that's a blast to sail. "When you're on the water, the

505 seems like the only boat on earth," says former Lindsay boatbuilder, Dave Dyson.

Besides, Tom Kivney adds, "with 31 years of experience, I think I'm getting

better." French legend Buffet's passion for the 505, which has brought him to 38

world championships, is an inspiration to all sailors.

Skippers range in size and are relatively easy to come by; 505

crews are the class stars. (Under class rules, skipper and crew trophies, are the same

size.) Several crews, such Martin, Alarie, and Lewis, own boats. And if you're planning to

attend the Worlds, having a good crew is crucial.

Two-time North American champ Macy Nelson lost his crew early in

the summer, a big blow to a well-prepared program. Then Nelson lucked into another good

crew, Finn sailor Geoff Ewenson, just before Hyannis. "Having a good crew makes all

the difference," says Nelson. "I've sailed with Alarie and Mills they just

make things easy." The 43-year-old veteran's regatta trials got worse when he blew

out his back just before the event. During the pre-Worlds, walking was difficult, hiking

impossible. But with the help of steroids, an anti inflammatory, and "a painkiller

cocktail," Nelson was determined to race in the Worlds. "It's been a rough year,

but my week's getting better. I think I'm ready for some heavy air.

It's

Wednesday, Race 5, and the big breeze everyone has anticipated since Sunday has arrived.

Postponement. Like big-wave surfers who travel long distances for epic surf, 505 sailors

pace the dinghy park awaiting their chance in the men-from-boys conditions. Big crews

smile. Small crews are surly. Race officer Dave Penfield, the 1979 world champion, is

pacing, too. He knows the meaning of a heavy-air race at the Worlds. It's a test: Whose

gear will hold up? Who's in shape? Who's the fastest?

Still postponed, the stories begin. "Remember the Worlds in

South Africa, 1979...Remember the 170-odd boats in England's 'race of the year'...In the

beginning, Howard was a surfer..I beat Paul Elvstrom by one point in 1983..Remember

getting arrested at our first 505 regatta." The stories, recycled from last year's

Worlds, get taller as the week goes on.

Postponement ends as the winds drop to a less-than-25 knot

average. At the gate start, the players are scattered throughout the fleet, ready to duck

and burst into clear air. Trotman and Mills climb to windward in their mid-fleet lane;

Barker, a few boats down, pokes ahead with the Yanks. At the windward mark, they're both

clear ahead of the fleet. Wtih 12 miles to go, it's a two-boat race. Trotman's lead

expands, then Barker takes advantage of their too-loose cover and sneaks by. Another win

for the Americans would have all but sealed the deal, but the Brits won't go easy.

Who's the fastest? Well, the Brits, first and third at the finish

of race 5, still rule in heavy air. But the Americans ("super-Yanks," according

to Masterman) have arrived. Trotman and Mills hold on to win after the 1-1-2 cushion;

Hamlin and Martin rally for second, the 45-year-old skipper's ninth top-five finish at the

Worlds; and Zani and Alarie are fourth, a few points back from Barker.

So what's next? "The thing about the 505," says Nelson,

"is there's always another Worlds."

|