|

A NEW DIMENSION IN SAILING Articles published in Sports Illustrated: April 3rd & 24st, 1961 (PDF document) by MORT LUND with GEORGE O'DAY Drawings by Tony Ravielli |

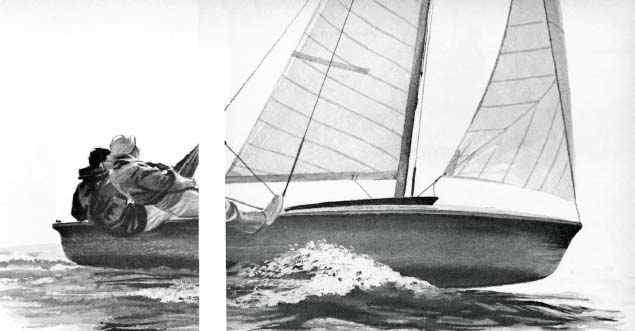

The

powerful hull at right, surging ahead like a surfboard, is one

of an exciting new type of sailing craft called planing boats.

Capable of moving at triple the speed of conventional boats,

they have advanced the art of sailing into a truly new

dimension. Until planing boats were developed (SI, April 28,

1958), the speed of a sailboat was limited by the length of its

waterline. Every boat moving through the water made a bow wave

and a stern wave (top

diagram, right). And once the boat reached a given

speed, it could not go any faster, because to do so it would

have to climb up its bow wave. Because of weight and the shape

of the bottom, the conventional displacement hull could not rise

out of its own wave trap. The planing boat, however, is designed

to escape the trap. Light in weight, with powerful sails and a

flat stern, it behaves like a displacement boat in light winds

(center

diagram). But when a puff hits, the force of the wind,

counter-balanced by the weight of the crew, pushes the boat onto

the bow wave. Then the flat bottom, instead of mushing down in

the water, forces the light hull toward the surface until it

pops out of the trap and skims along (lower

diagram) on the crest of its own bow wave. The key man

in the development of planing in the U.S. is

George O'Day of

Marblehead. As a salesman he has distributed more than 900

planing hulls. As a racing skipper he has won the Men's North

American championship in a Thistle-class planing boat. Last

summer, using the skills he refined in planing, he won an

Olympic gold medal in the displacement-type 5.5-meter boats at

Naples. At right and on the following pages, O'Day, with the

help of his Olympic crewman,

Dave Smith, demonstrates these

skills both for planing sailors who want to master their high

art and for sailors of conventional hulls who can use some of

these same advanced techniques to make their own boats go

faster.

The

powerful hull at right, surging ahead like a surfboard, is one

of an exciting new type of sailing craft called planing boats.

Capable of moving at triple the speed of conventional boats,

they have advanced the art of sailing into a truly new

dimension. Until planing boats were developed (SI, April 28,

1958), the speed of a sailboat was limited by the length of its

waterline. Every boat moving through the water made a bow wave

and a stern wave (top

diagram, right). And once the boat reached a given

speed, it could not go any faster, because to do so it would

have to climb up its bow wave. Because of weight and the shape

of the bottom, the conventional displacement hull could not rise

out of its own wave trap. The planing boat, however, is designed

to escape the trap. Light in weight, with powerful sails and a

flat stern, it behaves like a displacement boat in light winds

(center

diagram). But when a puff hits, the force of the wind,

counter-balanced by the weight of the crew, pushes the boat onto

the bow wave. Then the flat bottom, instead of mushing down in

the water, forces the light hull toward the surface until it

pops out of the trap and skims along (lower

diagram) on the crest of its own bow wave. The key man

in the development of planing in the U.S. is

George O'Day of

Marblehead. As a salesman he has distributed more than 900

planing hulls. As a racing skipper he has won the Men's North

American championship in a Thistle-class planing boat. Last

summer, using the skills he refined in planing, he won an

Olympic gold medal in the displacement-type 5.5-meter boats at

Naples. At right and on the following pages, O'Day, with the

help of his Olympic crewman,

Dave Smith, demonstrates these

skills both for planing sailors who want to master their high

art and for sailors of conventional hulls who can use some of

these same advanced techniques to make their own boats go

faster.

SPECIAL GEAR FOR PLANING

The 5-0-5 carries all the equipment and has the design

characteristics commonly found in planing boats. She has a flat

stern to help her get onto a plane. She weighs 280 pounds (compared

to 425 for a comparable nonplaning class, the Snipe) and has 150

square feet of sail in her mainsail and jib (a Snipe has 115).

Because of her light weight and her big sails, she needs special

gear to keep her upright. The most potent piece of equipment is

the trapeze

(1).

This consists of a wire attached to the upper part of the mast,

with a wide belt that snaps on at the lower end. In heavy winds

the crewman clips the belt to the wire and hangs out over the

windward side (above). There he can exert three times the

leverage of a man perched on the windward rail. The less

spectacular hiking straps

(2)

are canvas belts under which the legs can be hooked to allow

both the skipper and the crew to lean (hike) over the water from

the hips up. The extension tiller

(3)

lets the skipper control the boat while he is hiking. The boom

vang (4)

is a short wire that holds the mainsail in its best shape. The

trap-door bailers

(5) are a pair of hinged flaps held by

elastic cord (upper diagram, right) that can be released

(lower diagram) to drain the fast-moving hull if she

ships water.

1 Ready

to plane, O'Day and Smith sit on rail. Wind is broadside.

Smith holds jib sheet; O'Day holds main-sheet and extension

tiller, while he watches for dark patch on water that means

strong puff of wind is coming.

2 Wind

hits and boat accelerates. Both men move outboard, bringing

their ankles up against the hiking straps and leaning out

quickly. At same time O'Day slacks mainsheet about a foot, ready

to pull it in fast to help pump the boat onto a plane.

3

Breaking onto plane, O'Day pulls sail in quickly, and both men

hike far outboard. Boat now surges ahead on top of its own

bow wave, leaving typical flat wake as 5-0-5 jumps speed from 5

knots to 10 or more.

TAMING THE TRAPEZE

Trapeze is used only when wind is blowing so hard that hiking

with straps, as O'Day and Smith are doing in gentle gusts above,

will not keep the hull flat. Crewman, however, wears a wide

foam-padded belt continuously, whether it is attached to wire or

not. The wire � actually two

wires, one on each side of mast � is held secure at lower end by

elastic cord. Getting out over water is fast, tricky work. Here

O'Day momentarily relinquishes tiller to show proper procedure.

First, with belt hooked onto wire, O'Day, jib sheet and wire in

right hand, slides back

(A) to brace left leg stiffly

against trapeze block. Then

(B) O'Day pulls jib sheet

taut and pushes off with right leg. Next he swings over water

(C), keeping left leg stiff, right leg relaxed to act as

shock absorber. Coming back in

(D), he slips foot under

hiking strap before removing belt wire.

GETTING THE BOAT TO PLANE

Getting a boat to plane is fun in any circumstances, but in a

race it is absolutely essential, for the first boat up will

double the speed of its rivals. Therefore the skipper and his

crew must watch the wind and learn to feel when the boat is

going almost fast enough. In a 5-0-5 this will be at about 6

knots and requires a wind of at least 10 knots. The instant they

feel conditions are right, the men must lean far out, pump the

sails and try to bounce the boat out of the trough created by

its bow and stern waves and get it up onto a plane.

The most important factor in

planing, as in all sailing, is the direction and strength of the

wind. A planing boat reacts most efficiently to wind coming in

from slightly forward of broadside. Therefore, in the sequence

at left and below, O'Day and Smith bring the 5-0-5 broadside to

the wind. As a puff hits, they do a precisely timed,

simultaneous backward and outward hike to keep the boat on its

feet so its broad stern can help lift it up. On a gusty day,

when the wind first drops below planing strength and then rises

again quickly, the 5-0-5 will go on and off plane repeatedly.

The skipper and crew then have to move in and out constantly to

keep the hull flat on the water. If they move out too soon, the

boat will tip awkwardly to windward, spilling wind from the

sails and losing way. And if they move out too late, the boat

will miss the chance to get up; or at worst it will flip over,

leaving all hands paddling in the water.

STAYING ON A PLANE

Once the boat is on a plane, keeping it there calls for finesse

and judgment, especially in maintaining the best, most powerful

angle with the wind. As the 5-0-5 accelerates, the direction of

the wind experienced on board shifts toward the bow (small

arrows in diagram below left), even though the direction of the

true wind over the water (heavy arrow below) remains the same.

This new and varying wind direction is called the apparent wind

and is a combination of the true wind and the air which

naturally flows back as the boat moves rapidly forward. If the

boat is not handled properly, the apparent wind will eventually

swing so far toward the bow that the boat will slow down and

drop off its plane. Therefore, as the boat accelerates, O'Day

keeps the apparent wind at the correct angle, by driving off (veering

downwind). In the diagram, the second and third hulls from the

top show how O'Day keeps the apparent wind coming over the side

of the hull at a constant angle. As the boat speeds up, both men

have to hike out farther. For not only does the apparent wind

change direction, but the increasing speed of the boat itself

adds to the power of the apparent wind. When the wind drops off,

however, O'Day must sense the change immediately and swing the

boat back to the original course. The snakelike path that

results from driving off and coming back is typical of a

well-skippered. planing hull. The enormous advantage of keeping

the boat driving at top speed more than makes up for the curving

passage through the water.

1 In

steady wind, the boat planes perfectly, kept flat by hiking

of O'Day and Smith.

2 In

rising wind, O'Day drives (veers) off and slacks main. Both

hike out farther.

3 Under

control, O'Day pumps main to add speed as he continues to

drive hull off.

APPARENT WIND

shifts forward and then back, forcing boat to drive off and then

return to its original course.

RIDING

DOWN THE WIND

Three weeks ago on these pages, Olympic Yachting Champion George O'Day

introduced the art of planing, in which light, flat-bottomed boats like

the 5-0-5 (below) can be made to rise onto the surface of the water and

skim along at triple the speed of conventional craft. Now O'Day, with

his Olympic crewman Dave Smith, shows how to get even more speed out of

a planing hull, first by wave riding and then by setting and handling a

spinnaker. These advanced maneuvers are used only in downwind sailing,

and require a more sensitive touch than the basic lessons of Part I,

where the wind was coming from broadside or slightly ahead.

In the lakes and bays where planing boats usually are sailed, the waves

tend to be short and choppy like the ones shown here. Unfortunately,

these are the hardest to ride, since they lack power and hence cannot

carry the boat any great distance or lift its speed more than three to

four mph. Nevertheless, each wave, if ridden properly, can mean a gain

of a few yards; and over the full course of a race, these yards can add

up to victory. O'Day is particularly skillful at handling a boat in a

choppy sea. As each wave approaches, he catches the crest, holds it for

a moment, then drops of again, ready for the next one. So quickly do

O'Day and Smith manipulate the tiller and sails that the entire sequence

shown here takes no more than 10 seconds.

In a larger sea with more carrying power, the jobs of both the skipper

and crew are much easier. The sequence can last for half a minute or

more; and if the wind is blowing hard enough, a well-balanced boat can

hold onto a crest for nearly a quarter of a mile, skidding down the face

of the wave at 15 to 20 mph. A planing ride at these speeds is unlike

anything else in small-boat racing. A flat wake hisses out astern as the

boat surges forward with such steady power that she seems to be riding

on steel rails. One false swing of the tiller, however, and this

exhilarating charge downwind can come to a sudden, wet halt (see pages

50-51).

1 As a wave approaches from left, O'Day pulls tiller to start stern

swinging into crest.

2 With boat's stern toward swell, Smith and O'Day slack sails, get ready

to hike out.

3 When crest reaches middle of hull, men pull hard on sails for added

speed.

WAVES

FROM THE SIDE

The first move in riding waves that come from the side (as shown here)

is an abrupt turn to swing the broad stern of the boat into the crest.

When the wave hits, the stern rises and the hull gathers speed as it

starts to run down the front of the swell. To stay on the wave as long

as possible, Smith and O'Day pump the sails in hard, and lean (hike)

well out on the windward side, keeping their balance by tucking their

toes under the canvas hiking straps, just as they did in the first

planing demonstration in Part I.

RIDING WAVES, boat turns 20� off course in order to catch swells.

SHIFTING back and forth in cockpit, crewmen keep weight over peak of

wave.

1 Between waves, boat planes along at 10 miles per hour. O'Day and Smith

sit quietly in cockpit, ready to let out mainsail.

2 On crest, traveling now at 15 miles per hour, O'Day turns slightly off

the wind as both men slide their weight forward.

3 Hanging on as crest starts to leave, O'Day gives 5-0-5 last burst of

speed by quickly trimming both mainsail and jib.

4 Back in trough again, both men shift toward the rear of the cockpit as

their boat returns to normal planing speed.

WAVES

FROM THE STERN

When the swells are coming in from behind, there is no need to make a

vio-lent change of course since both the boat and the wave system are

going in the same general direction. However, when the first crest moves

under the boat, the skipper should turn slightly off course in a gentle,

even curve to keep the wind flowing into the sails at the best angle.

Veering off like this also prolongs the ride by sending the hull

slanting across the face of the wave rather than straight down it.

Although the maneuvering of the boat in this situation is comparatively

simple, the men aboard must be careful to keep their weight directly

over the crest so the boat balances properly throughout the ride. This

means they must slide forward and then backward inside the cockpit as

the wave surges past. The movements of both crewmen must be smooth and

steady, and their timing precise. Otherwise, the boat will wobble down

into the trough, losing as much as 50% of its speed, and perhaps the

race.

PLANING

WITH A SPINNAKER

The spinnaker (right) is a powerful, full-bellied sail set before the mast to

give extra speed going with the wind. Sailors of heavy conventional boats use

spinnakers on virtually all downwind runs; but planing skippers use them less

often for two reasons. First, the sail is so big that it can overpower a

sensitive boat like the 5-0-5 when the wind freshens. Second, by tacking (e.g.,

zigzagging downwind), catching the waves and keeping the boat planing, a skipper

like O'Day can often reach the finish line faster using a small jib than he

would sailing a straight course under a spinnaker. In light and medium winds,

however, O'Day finds that to keep the boat moving he must drop his jib and set

the big sail. And in very light air he has to pump the spinnaker (below) to get

the 5-0-5 up onto the surface where it can plane.

TECHNIQUE OF SETTING spinnaker is same for

planing boat as it is for any small craft (SI, March 2, 1959). When wind

strikes, sail spreads out and tends to lift upward. As spinnaker rises, Smith

and O'Day pull back on lines, stretching sail so it catches as much air as

possible. Going directly before wind (above), men balance boat by sitting on

opposite sides of mast, swinging tiller constantly to meet subtle wind shifts,

but moving sheets as little as possible to avoid spilling air from sail. When

breeze moves decisively to one side, however, crewmen shift to windward (left)

and trim spinnaker so that it stays full. Then if boat drops below planing

speed, O'Day gets it moving again by pulling back hard on one corner of

spinnaker. This quick pumping action gives the sail added lift, in same way

small boy gets kite to fly higher by tugging on string.

KNOCKED DOWN by sudden gust, O'Day and Smith

are already on high side of hull, ready to climb onto centerboard (below, right).

1 Mast and sail begin to rise out of water as both men put their full weight

onto the centerboard.

2 Half recovered from knock-down, O'Day starts back into boat; Smith stays on

centerboard.

3 O'Day clambers into cockpit while Smith, still hidden behind hull, continues

to pull downward.

4 Once aboard, O'Day moves to far side of cockpit to balance hull while Smith

climbs over gunwale.

5 Sails trimmed and bailers open, 5-0-5 drains herself dry as she quickly gets

up to planing speed.

SAILING

OUT OF A CAPSIZE

No matter how good he is, sooner or later anyone who goes out in a sailboat

turns over. But in a planing hull, a capsize does not mean the end of the race.

Practically all planing boats have built-in flotation tanks, and since the hulls

weigh so little, they float high in the water, even when swamped. If the crewmen

learn to move fast enough, they can get their craft upright without dropping too

far behind in the fleet. At left, the 5-0-5 has just gone over. As water pours

into the cockpit, O'Day and Smith scramble to the high side to keep the mast

from going under. Then they quickly pull the boat back on her feet, trim the

sails, and by opening the trap-door bailers (below), have the 5-0-5 up and

planing less than 30 seconds after she went over. END

□

Souped-up sailers

Hottest hulls on the Seven-Seas today

are the fast and unpredictable planing sailboats

An article published in Sports

Illustrated: April 28th,1958 (PDF document)

Page:

43 / 44 /

45

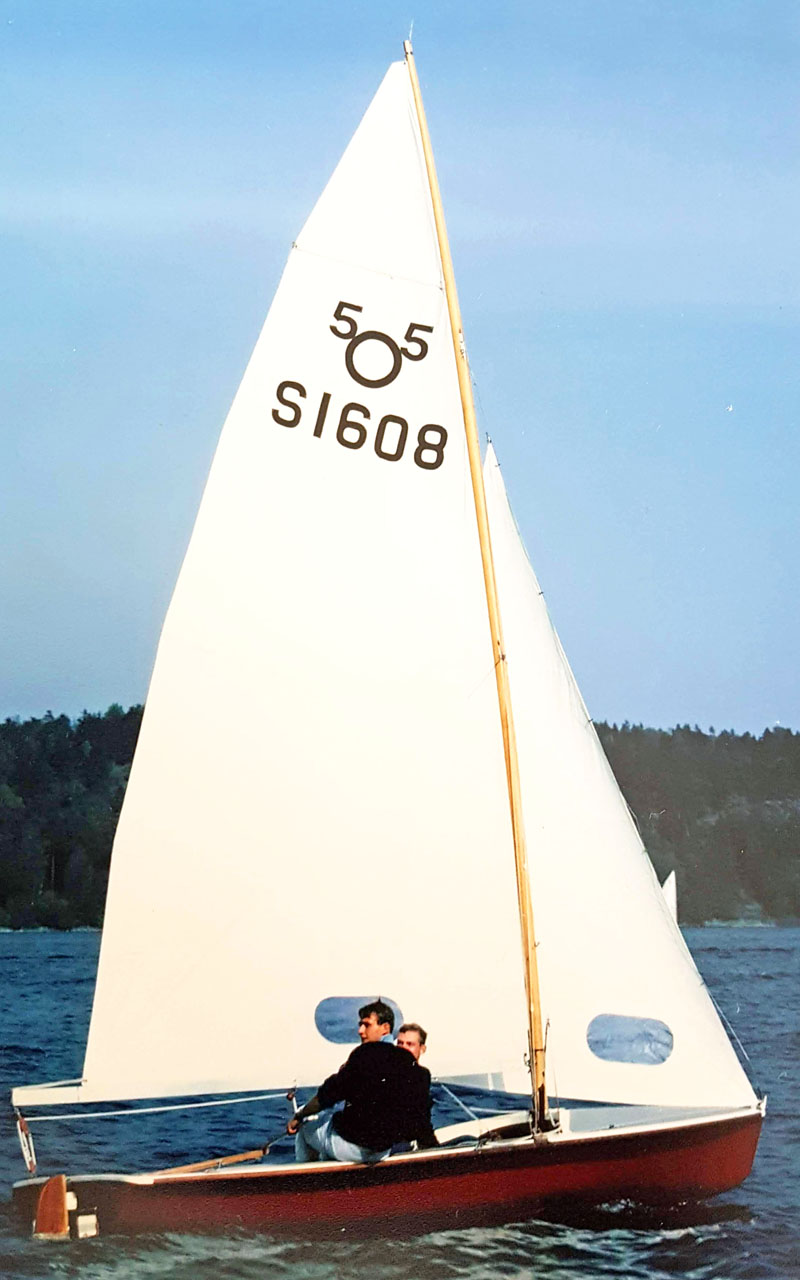

Berne Lindh &

Lars

Wiklund in 5-0-5 2297 'Cavalier'

Not always easy in a

strong breeze.

Preparing for a race

at Langedrag

in Gothenburg, 1963.

Torgny

Nordstrom (to the right) at Baggensfjarden in Stockholm in his first 505

S-1608,

"Parbleu"

□

SSSS 1962-2012

The Philberth brothers' memories from the early years

� Sv.505 F�rbundet �

Uppdaterad 2024-04-28